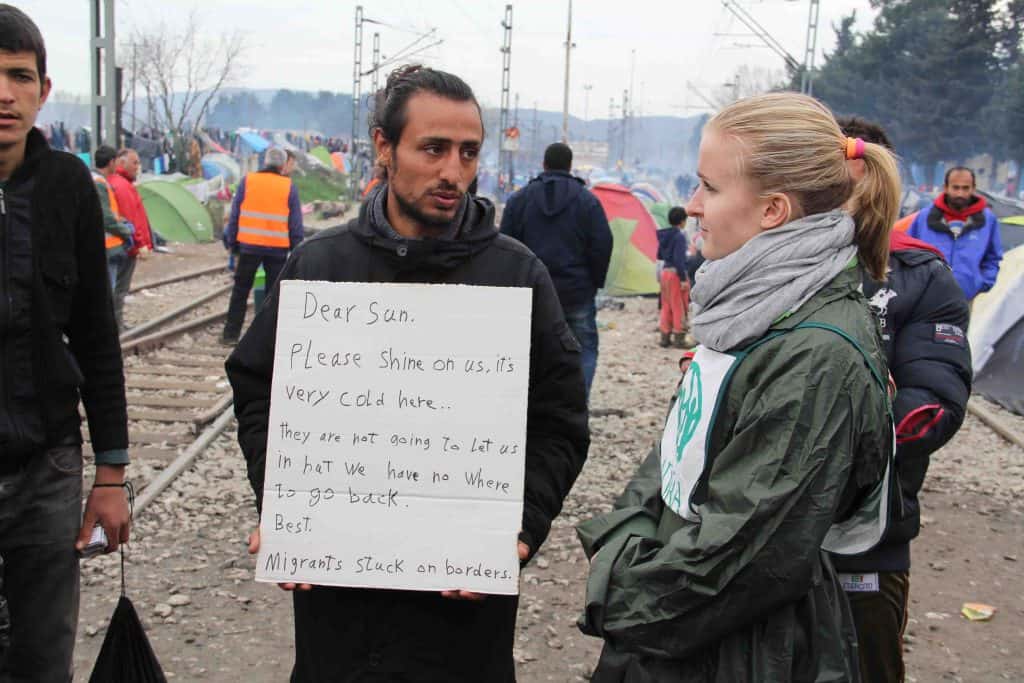

When Europe started closing its borders and refugees entering Greece became stranded, many of them congregated in Idomeni. The informal camp was the largest in Greece, with more than 10,000 people gathering at the Macedonian border hoping to be allowed to continue on their journey.

In an unofficial camp, there was no government assistance for services in the camp, and refugees were dependent on themselves or non-profit organizations like ADRA that offered assistance in the camp.

Serbian-Syrian translator Samir traveled to Greece shortly after Idomeni sprung up. He says that conditions had greatly improved in the camp, but that when he first arrived the situation was very grim.

“It was like a horror movie,” he said. “People were actually starving. There was no food being distributed in the camp. ADRA was one of the first NGOs there. We had a truck and when people saw us they ran after us. When we opened the door they pleaded with us, ‘Please give us something, we are hungry.’ There was a warehouse with all kinds of materials donated by individuals around Europe, so ADRA helped to distribute items to people who were in the most need.

“Another problem was the rain and the cold. I saw one man, shivering, wearing only short sleeves. I took off my jacket and gave it to him.”

It is a very different scene when we visit Idomeni a month later. When we get out of the van, we are greeted with hugs and smiles by children. After greeting us, they return to a large group of children gathered around a CD player. A young woman leads the children through the actions of much-loved songs like ‘The wheels on the bus’ and ‘If you’re happy and you know it’, which blare from the speakers. It is the first organized activity I’d seen in the camps, and the children seem to be enjoying the diversion.

Tents have sprung up everywhere in Idomeni, including on the train tracks. Here we meet Faaria. She is traveling with her sister, their husbands and their children. She has three children – two boys and a girl. She is also pregnant, but doesn’t know how many months. There are doctors in the camp but she doesn’t have access to equipment like an ultrasound machine. The hospital will only treat people in an emergency situation. They admit mothers in labor, but if they are healthy enough they have to go back to the camp with their babies the following day. Her sister was pregnant too, and had her baby five days ago.

We ask her about her life in Syria before the war. Her face lights up. “Beautiful! It was perfect!” she says in English. “After the war… oof.”

Faaria and her family left Syria 55 days ago. “The journey was tiring, very hard. You can imagine,” she says. “We made a plan with one smuggler to take us to the Turkish border by car. We left before dawn. When we arrived at the border, we had to wait a long time. The Turkish police didn’t want to let us inside Turkey.

“In the night a smuggler came and took us. We had to climb over a high barrier, and jump down the other side. There were a lot of police at the border. If they catch you they will hit you, so you had to run very fast. That’s the life of a refugee. It’s not nice at all. But if you don’t leave that way, you won’t get out.”

Her family was among the first to arrive in Idomeni. When they arrived there weren’t even tents there. Conditions were bad, and people were so depressed she says some people committed suicide by setting themselves on fire.

She is very worried about snakes, and has seen one very close to her tent. That night she had nightmares all night about snakes, and couldn’t shake the feeling that there was one slithering on her leg. She knows of one woman who found a snake in her tent. Thankfully she hasn’t had any snakes in her family’s tent, though they did find a scorpion in there.

She says that if people want to help them, help them to move forward. All she wants is safety for her children, nothing else. She has already lost two children – one-year-old twins who were killed in the bombing.

“If they’re human, they have to help us complete our journey.”

As we continue along the tracks, we walk alongside an old train which some refugees are living in. Two young sisters come out and want to play with us. They are delighted to be picked up and held.

As we get closer to the Macedonian border, we meet Abdul, who is from Syria. “It was so simple,” he said of life before the war. “It was like a paradise.” But then Islamic State militants came to their city. He is a teacher, and ISIS wanted him to teach in their schools. He refused. He fled Syria with his cousin, who is pregnant, and already a mother to three other young children. Ultimately they left for the sake of the children – Abdul said Islamic State militants were taking children and brainwashing them, and they didn’t want that for his cousin’s children.

But life as a refugee was harder than they expected. They had to throw most of their belongings into the sea when they crossed the Mediterranean by boat, so they are in need of clothing. They are suffering from skin problems like scabies. The shelter is not good. There is not enough food. The children are underweight. Abdul also says there is no consideration for people with special needs, like pregnant women and children. He describes the conditions in the camp as “very, very, very, very, very bad”. He said he would rather sleep with the cows in the field in Syria than continue living in this camp.

“When we left Syria we were so depressed. When we got to Turkey we felt relieved, and even happy when we reached Greece. Now I would have preferred to die under the bombing than be here.”

ADRA was able to provide some essential items to Abdul’s family. The relief they felt, at having even one small need met for the time being, was obvious.

Before we leave the camp, we spend time with some brothers. One was a barber in Syria, and is giving his brothers haircuts. He brought his clippers all the way from Syria, but they no longer work so well. He asks if we can get him some new ones.

NGOs like ADRA are busy working in numerous camps in Greece, doing their best to provide for the basic needs of the refugees. But in the midst of such need, it is easy to forget how valuable items of comfort can be, especially things that can restore a sense of normalcy amidst great disruption. For this man, he just wanted new clippers so he could continue to cut his brothers’ hair.

*Names have been changed to protect identities*